(Editor’s note: Greetings and thank you from the BOOM. One of our readers asked for the following article to be retracted or the section on Ty Cobb removed because it perpetuates an unproven mythology of Ty as a person and player. They refer to the book written by Charles Leehrsen, Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, in which he argues that the stories of Ty as a violent racist are largely, if not entirely, untrue, and that there is even evidence that Ty could have been opposed to racial injustice, like the segregation of Baseball.

And while Mr. Leehsen’s thesis may in fact be true, we, like him, do our research and we respectfully disagree with his argument. Ty was a racist and violent, some could argue, murderously violent. Unfortunately, all we have is circumstantial evidence to demonstrate the character truths of the man. Nonetheless, we are glad to have an opposing viewpoint that is so well researched and chooses a challenging position to a very complicated subject.

Finally, Ty Cobb, is not the only one. There was a system of racism that was perpetuated within the MLB for nearly sixty years. The kind of system that can only be maintained if those in power are 1) aware of it 2) support its purpose. There is no doubt many more than the four men that are mentioned in the following are guilty of being white supremacists. The four in question were just more obvious about their views. We hope, as always, that you enjoy the following. BOOM)

Watching Major League Baseball’s World Series, it’s difficult not to get drawn into the mystique, or maybe more accurately, the mythology of the so-called, “national pastime.” Since its inception in the middle of the 19th century, baseball has been about one thing, inclusion. All you need is a stick and a rock and a small piece of space, and you have the makings of a baseball game. Anyone, regardless of gender or race, or economic circumstances, can play baseball.

It is truly one of the greatest inventions of humankind.

In America, it is the superlative American Sport.

A container and curator of the American experience, it holds a very privileged place as a reflection of our culture and society. In this way, baseball acts like a mirror, reflecting those issues that are foremost in the American mind. Take for example the most recent world series between the Atlanta Braves and the Houston Astros. Is it surprising that the Atlanta Brave “tomahawk chop” has attracted so much controversy? Not when one considers how systemic racism has become one of the defining issues for America in the 21st century.

In the past decade, American’s have demanded that dozens of pieces of historical materiality, such as statues and paintings, be removed from publicly accessible areas, including parks, government buildings, publicly funded institutions, because they reflect problematic themes that have been deemed insensitive to under-represented populations.

For example, on September 8, 2021, a “12-ton…statue”[1] honoring the former head of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, General Robert E. Lee, was removed from Richmond, Virginia’s so-called Monument Avenue, where it had stood for over one-hundred and thirty years. Despite General Lee’s significance as one of the most important military figures in American history, the monument had long been viewed as a “symbol of racism and oppression…[an] idol of white supremacy.”[2]

But it wasn’t until the murder of George Floyd, and the re-emergence of the movement known as Black Lives Matter in 2020, that talk of its removal became an American, socio-cultural cause cé·lè·bre. The removal of General Lee’s controversial sculpture and pedestal seemed to be the pinnacle of a nationwide effort to eradicate all vestiges of racist symbolism. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, “168 Confederate symbols [have been] renamed or removed from public spaces…”[3]

With all the scrutiny on American institutions, it seems reasonable to expect that Major League Baseball (MLB), and its famous museum, the Hall of Fame (HOF), would be subject to the same kind of racial-scrubbing that has occurred throughout the country. Sadly, the opposite is true, instead of ridding itself of the remnants of its racist past, the MLB and its HOF seem content to simply ignore the issue and pretend that they are exempt from such criticism.

For almost fifty years, the Hall of Fame has endeavored to “honor…and immortalize (italics mine)” its inductees as representative “of the highest mark of achievement in the game”[4] that, for over a century, has been widely recognized as America’s, “national pastime”.[5] As “keeper of the game”[6] the Hall of Fame’s self-proclaimed, three-fold mission has been “preserving [baseball’s] history…honoring excellence [amongst the baseball community]…[and] connecting generations [of its fans].”[7] It is for these reasons, the HOF holds a unique and some would say “hallowed” place within American society and culture.[8]

And yet, it continues to honor people everyone (by everyone I mean baseball historians, players of the game, coaches, GMs, etc.) know were violent and hate-filled white supremacists, who openly mistreated Black Americans because of the color of their skin.[9]

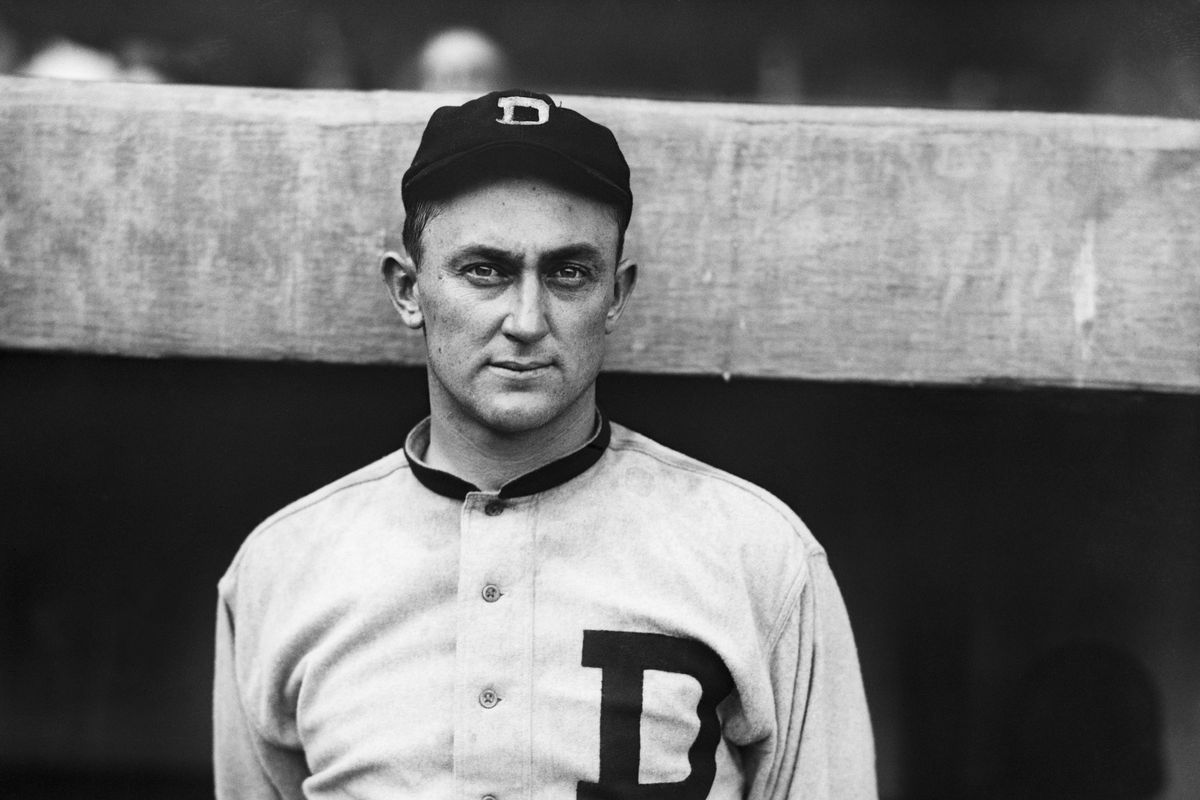

Perhaps the most egregious example is Ty Cobb.

To call Ty a ‘racist’ would only have pissed him off. He was a full-fledged member of the white-supremacy movement that established itself during Reconstruction and led to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

In his book, Baseball as I have Known It, renowned baseball journalist and historian Fred Lieb wrote, “Ty had a contempt for Black people and in his own language, ‘he would never take their Iip’… I don’t know if [he] was a Klansman but I suspect he was.”[10]

Ty was also violent.

Of course, it was downplayed and marginalized in the media because, just like now, NO ONE really wanted to talk about racism and baseball, the gentleman’s agreement[11] made sure of that. But just as Ken Burns’ asserts,[12] and I agree, Ty Cobb is a stain upon the MLB as the American, national pastime.

In an era in which America is demanding its institutions rid themselves of any racist iconography, how is it possible that a man like this could still be in the Hall of Fame?

The answer is simple. No one wants to talk about it. Not the team owners, not the players, not the media, not the fans, not the NAACP, not BLM; nobody wants to talk about Ty Cobb or the others.

It reminds me of Baseball’s first gentleman’s agreement[13] when, back in the late-19th century, white baseball owners in both the major and minor leagues, struck a deal to prohibit the hiring of black players. Even though everyone knew of the arrangement including the owners, the players, the commissioner, and the media, few ever complained. In fact, some in the media became apologists for segregation, more or less parroting[14] what the owners argued was the real reason for why Black players didn’t play in professional baseball, because they weren’t good enough.[15]

The leagues would remain racially segregated for nearly 60 years until Jackie Robinson played his first major league game for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946.[16]

And yet, even though it has been integrated for over 80 years, Major League Baseball stubbornly refuses to free itself of the memories of its racist origins by continuing to honor individuals who represent the worst of America’s racist past.

Why? Because the Gentleman’s agreement of the 19th century continues to exist in the silence of those who cannot or will not hold baseball up to the same standards as other American institutions.[17] This includes the ownership, management, player personnel, and the media. By refusing to hold Baseball accountable, leaders of sports media like ESPN and Sports Illustrated have made themselves complicit to Major League Baseball’s gross racial insensitivity.

They’re tearing down statues in Virginia, they’re pulling down paintings at the Capitol, but no one wants to remove Ty Cobb from the Hall of Fame.

For six decades, the MLB excluded thousands of American citizens from participating in the national pastime because of the color of their skin.[18] For it to continue as America’s socio-cultural analogue, it must now finish the work of history and remove the shadows of hate that continue to darken its halls.

[1] https://abcnews.go.com/US/virginia-remove-12-ton-robert-lee-statue-state/story?id=79862294

[2] See note 1.

[3] https://www.splcenter.org/presscenter/splc-reports-over-160-confederate-symbols-removed-2020

[4] https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers

[5] https://baseballhall.org/about-the-hall

[6] See note 4.

[8] See note 4.

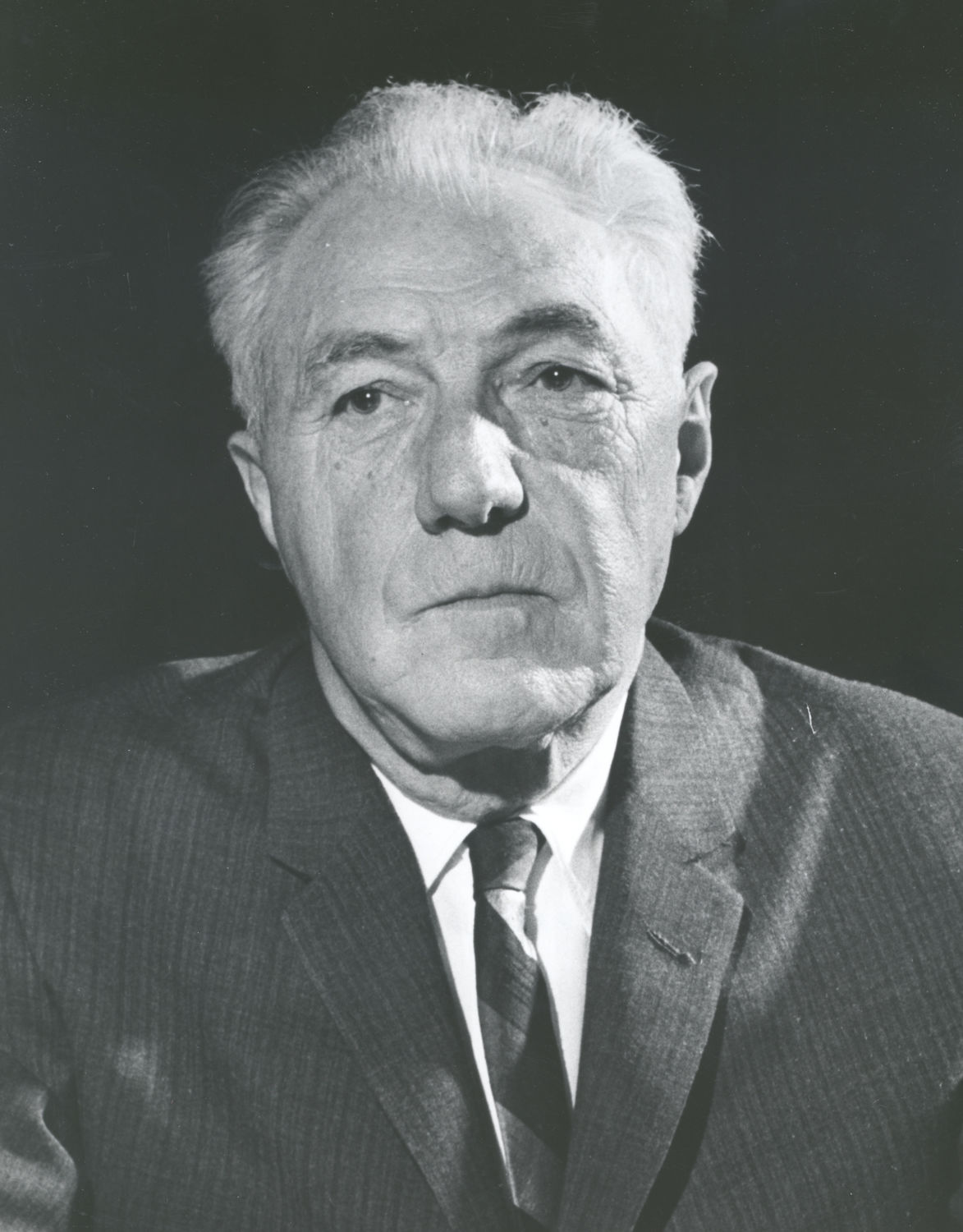

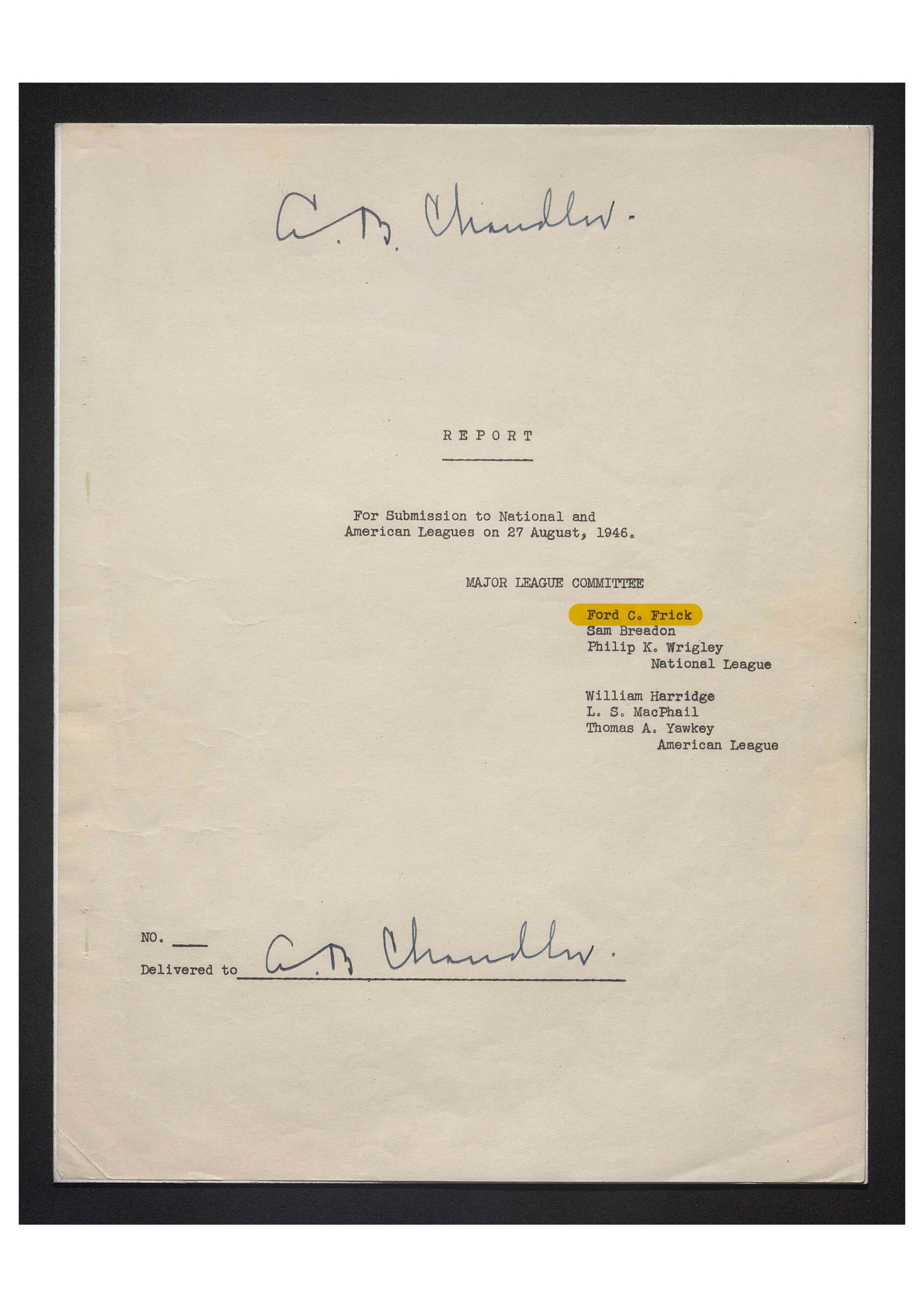

[9] Famed baseball journalist, Fred Lieb claimed both Tris Speaker (HOF, 1937) and Roger Hornsby (HOF, 1942) were members of the KKK (Lieb, 54). It was once said of Cap Anson (HOF, 1939), “…[he] was one of the prime architects of Baseball’s Jim Crow policies…” and had, “an intense hostility toward blacks” (Tygiel, 14). This means that of the first 27 inductees into the Hall of Fame, between 1936-42, four were hostile white supremacists. Given Baseball’s early history, there are more than likely others that should be added to this list. Kenesaw Landis, was another major figure in the fight to keep baseball white; (https://www.witf.org/2020/06/30/a-dark-past-mvps-say-time-to-pull-kenesaw-mountain-landis-name-off-plaques/). In a recent article for the BOOM, I discussed the segregationist period just prior to Jackie Robinson and the ugly history of the MacPhail Report, a terrible reminder of Baseball’s institutionalized racism (https://www.boomsalad.com/english/nonfiction/fordfrickaward).

[10] Fred Lieb, Baseball as I have Known It, (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1977), 54.

[11] Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 13. This subject will discussed in detail later on in this essay.

[12] Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns, Season 1, Ep. 3, The Faith of Fifty Million People: 1910-1920, Directed by Ken Burns, 1994, DVD. 15:46.

[13] Tygiel, 13.

[14] The Sporting News, August 6, 1942 edition, in an OP-Ed entitled, “No Good From Raising Race Issue”, gave a lengthy rebuttal to those calling for the integration of baseball. Not coincidentally, their arguments would closely resemble those of the owners and league presidents who favored segregation, as detailed in the MacPhail Report of 1946. (Tygiel: 38, 39).

[15] See the BOOM’s discussion of the MacPhail report (https://www.boomsalad.com/english/nonfiction/fordfrickaward/)

[16] https://www.boomsalad.com/english/nonfiction/fordfrickaward

[17] Speaker Pelosi orders the removal of paintings from the U.S. Capitol building. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/18/us/politics/pelosi-confederate-portraits-house.html

[18] Tygiel, 30.