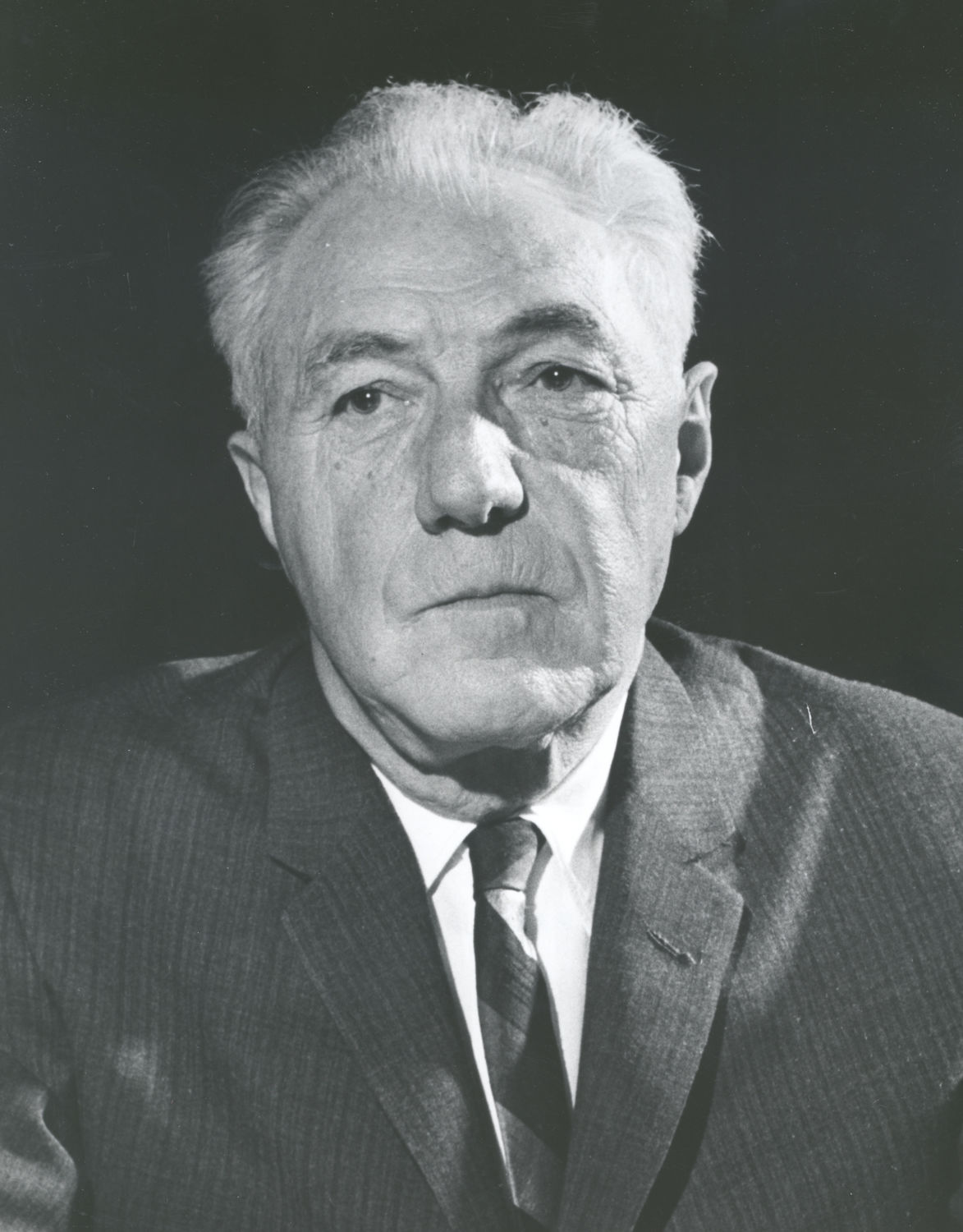

Since 1978, Major League Baseball (MLB) has sought to recognize the careers of sports broadcasters and journalists who it claims have made “major contributions to baseball”[1] by honoring them with what is known as the Ford C. Frick Award. Named after the former MLB Commissioner, National League President, and Hall of Fame inductee. The award’s recipients include many of baseball’s most influential and well-known broadcasters, such as Mel Allen (1978), Red Barber (1978), Vin Scully (1982), Jack Buck (1987), Dick Enberg (2015), Bob Costas (2018), and just recently, Al Michaels (2021).[2] Understandably, it is considered one of the MLB’s most prestigious awards conferred upon any non-player. And yet, for many, it represents an unfortunate, and unsightly reminder of Baseball’s racist history.

How so?

Simply put, in honoring the memory of Mr. Frick in this way, the MLB is, in effect, celebrating a well-known segregationist and white supremacist. And while many in the baseball community may object to this characterization, they cannot argue with the historical record detailing Mr. Frick’s important role in upholding the League’s policies regarding segregation during the middle of the twentieth century. Perhaps the most infamous example is his involvement in the creation of the so-called “MacPhail Report” of 1946.[3]

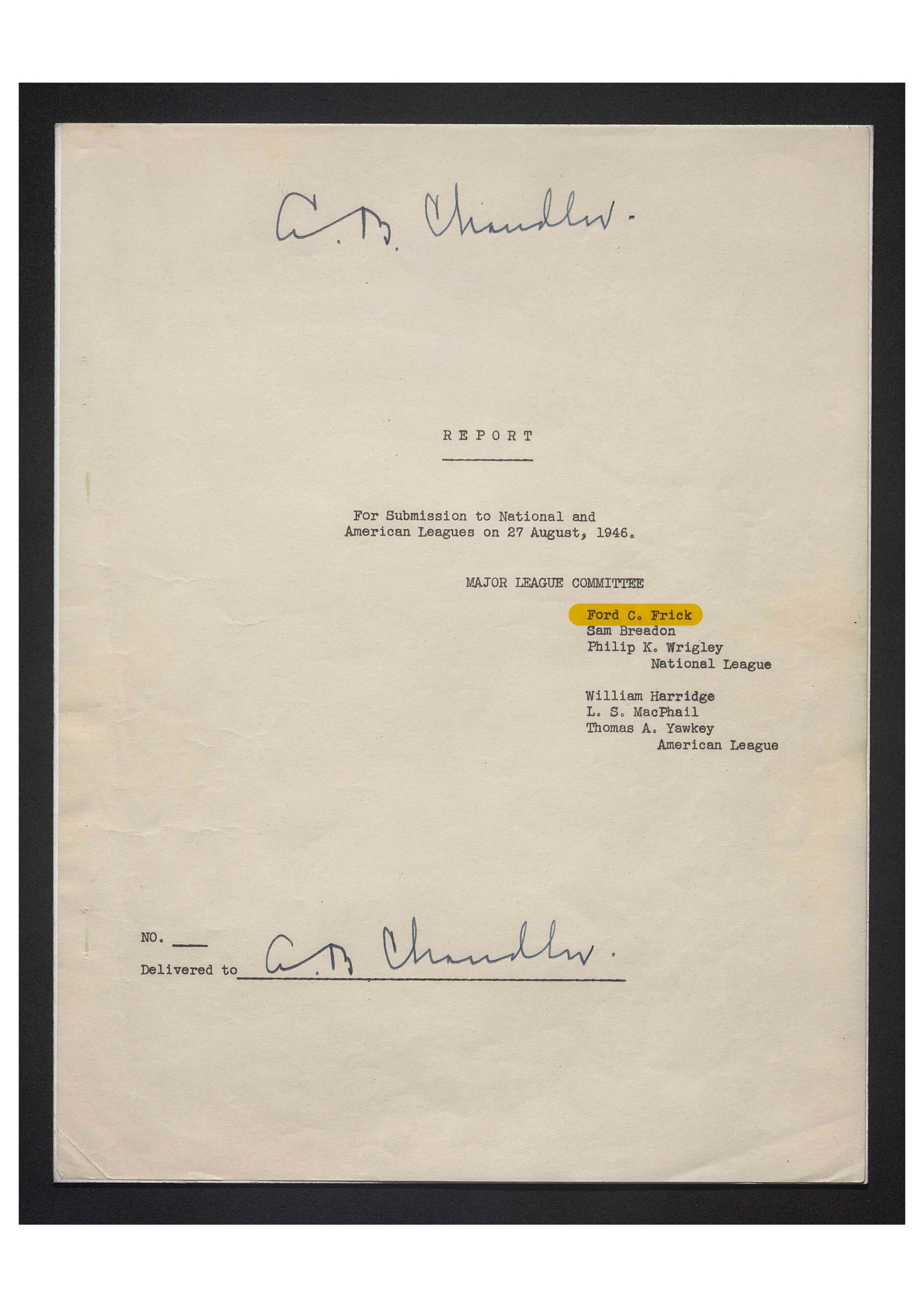

According to the late, baseball historian Jules Tygiel, “On July 8, 1946…the National and American Leagues established a joint steering committee ‘to consider and test all matters of Major League interest and report its conclusions and recommendations.’”[4] Amongst the numerous issues under consideration was the widespread practice of racial segregation, what the committee later referred to as the “Race Question.”[5] The year prior to the committee’s creation, Branch Rickey had famously broken MLB’s so-called “gentleman’s agreement”[6] by signing the now legendary, Jackie Robinson to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

According to Branch Rickey biographer, Murray Polner, the formation of the committee was, in many ways, a response to Rickey’s actions and an effort by the other owners and Baseball’s leadership “to keep [Major League Baseball] lily-white.”[7] Thus, the league appointed owners Larry MacPhail (Yankees), Thomas Yawkey (Red Sox), Sam Breadon (Cardinals), and Philip Wrigley (Cubs), along with both the President of the National League, Ford Frick, and American League, William Harridge, as members of the committee, with MacPhail“ elected [as] chairman.”[8]

Over the next six weeks, the committee met on several occasions and then presented their findings in the form of a 25-page report at an owner’s meeting held in Chicago on August 27, 1946. In the Forward of that report, the committee acknowledged that “Baseball…[was] under attack…” and that “Its right to survive as it ha[d] always existed [was] being challenged by rapidly changing conditions and new economic and political forces.”[9] Amongst these various challenges was the threat of integration, for which the committee sought to provide, “Methods to protect Baseball from charges that it [was] fostering unfair discrimination against the negro by reason of his race and color.”[10]

In subsection “E”, under the heading “Race Question”, the committee outlined the primary reasons, they believed, justified the continuation of the Major League’s informal policy of segregation. The first involved the fans. According to the report:

A situation might be presented, if Negroes participate in Major League games in which the preponderance of Negro attendance in parks such as the Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds and Comiskey Park could…threaten the value of the Major League franchises [with regards to white fans].

In other words, since the majority of those who attended the games were white, the committee feared that integrating the teams would lead to more Black fans attending. The result of which might prevent white fans from attending games all together. This, they argued, would no doubt have a deleterious effect on a team’s ticket sales and revenues.

The second reason given by the committee emphasized the “qualifications [or, lack thereof] of Negro players.” It stated:

The young Negro player never has had a good chance in baseball. Comparatively few good young Negro players are being developed. This is the reason there are not more players who meet major league standards in Negro leagues.[11]

Negro players, the report contended, lacked “the technique, the coordination, the competitive aptitude, and the discipline” necessary to play in the Major Leagues. One of the reasons cited was the Negro player’s lack of “minor league experience”. Of course, the committee failed to mention that the reason the Negro player had no experience in minor league baseball was because it, like the MLB, was also segregated.

Thus, the primary reasons proffered by the committee for why Black players couldn’t and shouldn’t play in the Major Leagues were, in the first instance, clearly racist, and in the second, promoted an overtly white-supremacist ideology. Despite these facts, at the end of the meeting, all the attendees were asked to sign the report as evidence of their agreement with its contents. Everyone (except for Branch Rickey), signed, including Ford Frick.[12]

Since then, many have attempted to defend Mr. Frick’s complicity by pointing to his actions after that infamous meeting in Chicago. For instance, some refer to a situation that occurred less than a year later when it was rumored that players on the St. Louis Cardinals were contemplating a strike if they were forced to play against Jackie Robinson. As National League President, Mr. Frick is reported to have instructed Cardinals’ owner Sam Breadon (another co-signor of the MacPhail report) to “Tell [the mutinous players] that if they go on strike, for racial reasons, or refuse to play in a scheduled game, they will be barred from baseball even though it means the disruption of a club or a whole league.” Murray Polner called it “Frick’s finest moment.”[13] And yet, while Mr. Frick’s words may seem to disprove any racist inclinations, one must ask, what choice did he have?

With Robinson now a fully-fledged MLB player it’s not as if Mr. Frick could have ignored the threat that a player walkout would have meant to the National League as a whole. The horse was already out of the barn. Moreover, it’s not as if his threat could be interpreted as some anti-racist polemic. Essentially, he was reminding the players that they were contractually obligated to play “scheduled games” regardless of who was playing on the other team. A more telling example of Mr. Frick’s views on race occurred years earlier, in 1943. According to Murray Polner, Bill Veeck Jr. sought to purchase the pitiful Philadelphia Phillies with the intent of “stock[ing] it with Negro players.”[14] When Frick learned of the plan, he, along with Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, blocked the sale to Veeck so as to prevent him from “contaminating the league [with Negro players].”[15]

The point is, regardless of Frick’s stand after the admittance of Jackie Robinson, his involvement in the formulation of the so-called MacPhail Report cannot, and should not, be ignored or excused. He helped to write it and then signed it, and in so doing, became an accomplice to one of the most disgraceful attempts to prolong a form of systemic racism that to this day is rightly viewed with disdain and disgust.

How then can the MLB defend itself for allowing something like the Ford C. Frick Award to continue to exist? It has been 75 years since that infamous day in Chicago, and yet, in honoring Frick with his own award, the MLB willfully ignores the man’s history as a racist. Perhaps even more shameful than the award itself is the fact that not a single Black journalist has ever received it. Thus, the Ford C. Frick Award has become nothing less than a pantheon of celebrated white men. Even if all the recipients are men worthy of recognition, the optics are very troubling.

Which begs the question, how do historians of the game, people who know Frick’s history, like Bob Costas allow themselves to be associated with it? It’s a shame and an embarrassment to baseball and an affront to all minority journalists who cover the game. Simply put, the Ford C. Frick Award is an unsightly and unfortunate reminder of Major League Baseball’s racist history, one that needs to be done away with.

_________________________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Major League Baseball, “Ford C. Frick Award”, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/awards/887

[2] Major League Baseball, “1978-1979”, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/awards/887#1978—79

[3] MacPhail Report. August 27, 2021 marks the 75th anniversary of the MacPhail Report.

[4] Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 82.

[5] Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 83.

[6] Doug Pappas, “The MacPhail Report”, Outside the Lines (SABR, Summer 1996), (http://roadsidephotos.sabr.org/baseball/MACPHAILREPT.htm

[7] Murray Polner, Branch Rickey: A Biography (New York: Signet, 1983), 187.

[8] Tygiel, 82-83.

[9] MacPhail Rpt. Pg.2

[10] MacPhail, 3.

[11] MacPhail, 19.

[12] Polner, Branch Rickey, 187.

[13] Polner, 198.

[14] Polner, 152.

[15] Tygiel, 41.