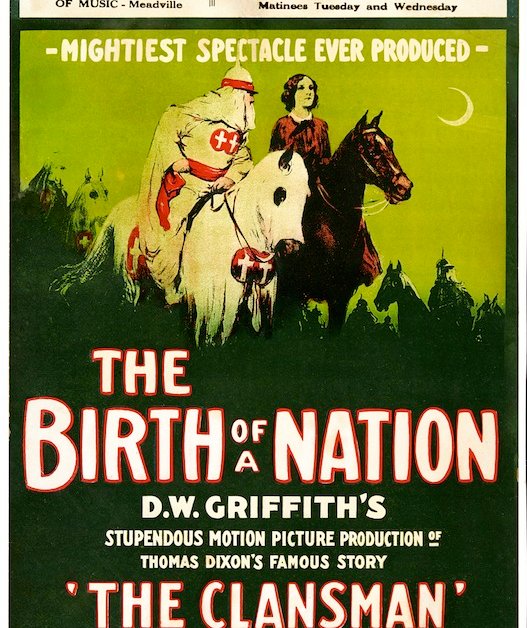

As a film historian I am intensely aware of the inherent flaws of the cinematic narrative. The fact that it deals mostly in hyperbolic stereotype has been the Achilles heel of all popular film since the earliest iterations of the modern film paradigm. The classic example is of course D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. From a 21st century perspective, the use of so many disturbing and exaggerated racial stereotypes is offensive to the postmodern sensibility. And yet not much has changed when it comes to Hollywood’s reliance on and perpetuation of ugly and inaccurate stereotypes. A prime example is the film Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby.

As a film historian I am intensely aware of the inherent flaws of the cinematic narrative. The fact that it deals mostly in hyperbolic stereotype has been the Achilles heel of all popular film since the earliest iterations of the modern film paradigm. The classic example is of course D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. From a 21st century perspective, the use of so many disturbing and exaggerated racial stereotypes is offensive to the postmodern sensibility. And yet not much has changed when it comes to Hollywood’s reliance on and perpetuation of ugly and inaccurate stereotypes. A prime example is the film Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby.

I remember the first time I watched the tale of Ricky Bobby, like many around the world, I found the comedy to be both outrageously funny and socio-culturally accurate. It was one of my all-time favorite comedies and I owned the regular and widescreen DVD versions, which I watched on a regular basis. Though I have family that lives in the Southeastern United States and are fervent NASCAR fans, I accepted Adam McKay and Will Ferrell’s vision of Southern culture without question. In other words, I allowed myself to believe that their version of the South, though a parody, was largely anchored in socio-cultural truth.

Thus, when we first encounter Ricky’s transient and criminal father, Reese Bobby, at his son’s school, or later, when we see Ricky Bobby’s first race, I laughed, just like everyone else, because I believed that no matter how outrageous their behavior, it was all based on a socio-cultural reality as to how Southerners are supposed to act. But that was fifteen years ago, and a lot has changed since then.

For instance, cultural movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have brought increased scrutiny on media productions like feature films and how they portray individuals representing minority and formerly marginalized communities like LGBTQ. More and more, the viewing audience and critics have become highly aware of the damage that ugly stereotypes cause to the individuals and communities they claim to depict. The argument from producers of film and video, that they were just having fun is no longer satisfying when one realizes the degree of harm that denigrating another culture, race, or community through the cinematic arts can do. Again, I refer to the ultimate example, Griffith’s disgraceful masterpiece The Birth of a Nation. Productions like Talladega Nights are only a more recent version of that terrible and divisive paradigm.

Recently, many have argued that comedy should be immune from socio-cultural critique and condemnation. Pundits of culturally problematic productions have sought to protect comedy as the great equalizer: comedy laughs at everybody, they insist. And yet, when one considers the trajectory of modern comedies, it becomes clear that they are not laughing at everybody. Comedians have long been under the delusion that they are the guardians and purveyors of the Freudian wit: a higher consciousness of the true, ironic nature of life and society. Thus, they have promoted themselves as better than the rest of us because of their unvarnished insights into the foibles of the human experience. Nothing could be more disingenuous.

Society and culture are finally coming to the realization that modern comedy is primarily about othering. Which is to say, that it is about making fun of someone else because of who they are, the culture they belong to, or their physical appearance and mannerisms. Comedy uses these distinctions as a means of differentiating between hero and villain, between who is admired and who is laughed at. Talladega Nights is an important example of this dichotomy and the socio-cultural deception that it perpetuates.

The only thing southern about Will Ferrell is his birthplace in Southern California. Likewise, Adam McKay is an old-school northerner from Philadelphia. Neither of these men could be, or would be considered, in any professional context, experts of the South. Their portrayals of the Southerner, therefore, are largely based on antiquated stereotypes that originate in the Civil War. Southerners are thus depicted as stupid buffoons who are socially backwards, naïve, and dangerous. All Southerners, including the women and children, are portrayed with this lens. Even Ricky’s mother, a kind of heroic outlier to the Southern reality cannot help but slap her grandsons in the face when disciplining them for their misbehavior. Ironically, it’s intended as a moment of high comedy and yet, comes off as disturbing and unnecessary.

From his name, a combination of two first names, to his upbringing: a single white trash mom in a poor town, to his homophobic hatred of so-called evolved culture (think of the bar scene when Ricky meets Jean Girard for the first time and his reaction to jazz music), Ferrell and McKay have made it clear that they believe the South is against everything progressive. The Southerner is, according to Ferrell and McKay, hopelessly locked in a time of good ol’ boys, fast cars, and loose women. In other words, a time of homophobia, xenophobia, misogyny, self-delusion, and a reckless disregard for the law.

“What about the protagonist/antagonist of the film, the French F1 driver, Jean Girard played by Sacha Baron Cohen? Isn’t he also depicted as a stereotype?” The easy answer is “yes” but in acknowledging that fact we risk overlooking how the stereotype is ennobled through its hyperbole. Girard has culturally iconic friends like Elvis Costello and MOS DEF. His marriage partner raises and trains world-class German Shepherds. They are open and unapologetic about their homosexuality. They do not watch low-brow films like Highlander. They like Jazz, macchiatos, and Perrier mineral water. More importantly, Jean is a champion F1 driver, widely considered the most technologically advanced motorsport in the world. He isn’t so much a character as a reflection of everything that Ricky Bobby, and thus, the South, according to McKay and Ferrell, is not but should be. In this way, Jean is representative of how McKay and Ferrell see themselves: enlightened, unapologetic, elitist neo-Northerners mocking the American South.

When I watch Talladega Nights now, I feel ashamed by the knee-jerk laughter that comes so easily at the expense of Southern culture. I feel exploited by McKay and Ferrell’s obvious efforts to denigrate one of the oldest examples of American culture and society. Moreover, I am saddened by the fact that American comedies continue to rely on a type of hurtful and ugly othering to manufacture laughs. It reminds me of when I was a middle-schooler watching the Bad News Bears, starring Walter Matthau, with a friend of mine that was obese. When the comedy shifted to making fun of the fat kid on the team, we both laughed and yet, I couldn’t help feeling bad for laughing. Moreover, I couldn’t help but wonder if my friend was laughing because he really thought it was funny or because he didn’t have a choice. Back then, as now, everyone laughed at the fat kid.