BOOM: That’s a very interesting comment, would you say, then, that another one of the weaknesses of past research into violent-video games and their effect on behavior, is that they lacked the necessary granularity into the lives of their subjects to arrive at anything truly conclusive?

Dr. Ceranoglu: Yes, that’s part of it. When we look at video games and its effects on mental tasks and cognitive tasks, and sleep, time and again, we found out that it’s not just whether the subject is playing video games or not, or which game [she or he] plays, but rather, it is the circumstances in which that game is being played. Where is the child playing? Who are they playing with? [What time] is the child playing? And ‘how’ is the child playing? Is it competitively [against another player] or solo? Is the child playing with a friend or are they playing with a stranger? Is the child playing in her or his bedroom, or the living room?

BOOM: In other words, if I understand you correctly, the situational and personological inputs of the player and their internal state, far outweigh, in terms of influence, any media exposure that is occurring while playing the game?

Dr. Ceranoglu: Yes. I would add to that, that we also know there are characteristics inherent to the person playing that determine the effects of the video game on that person, such as autism, ADHD, or other Disruptive Behaviors Disorders (DBD).

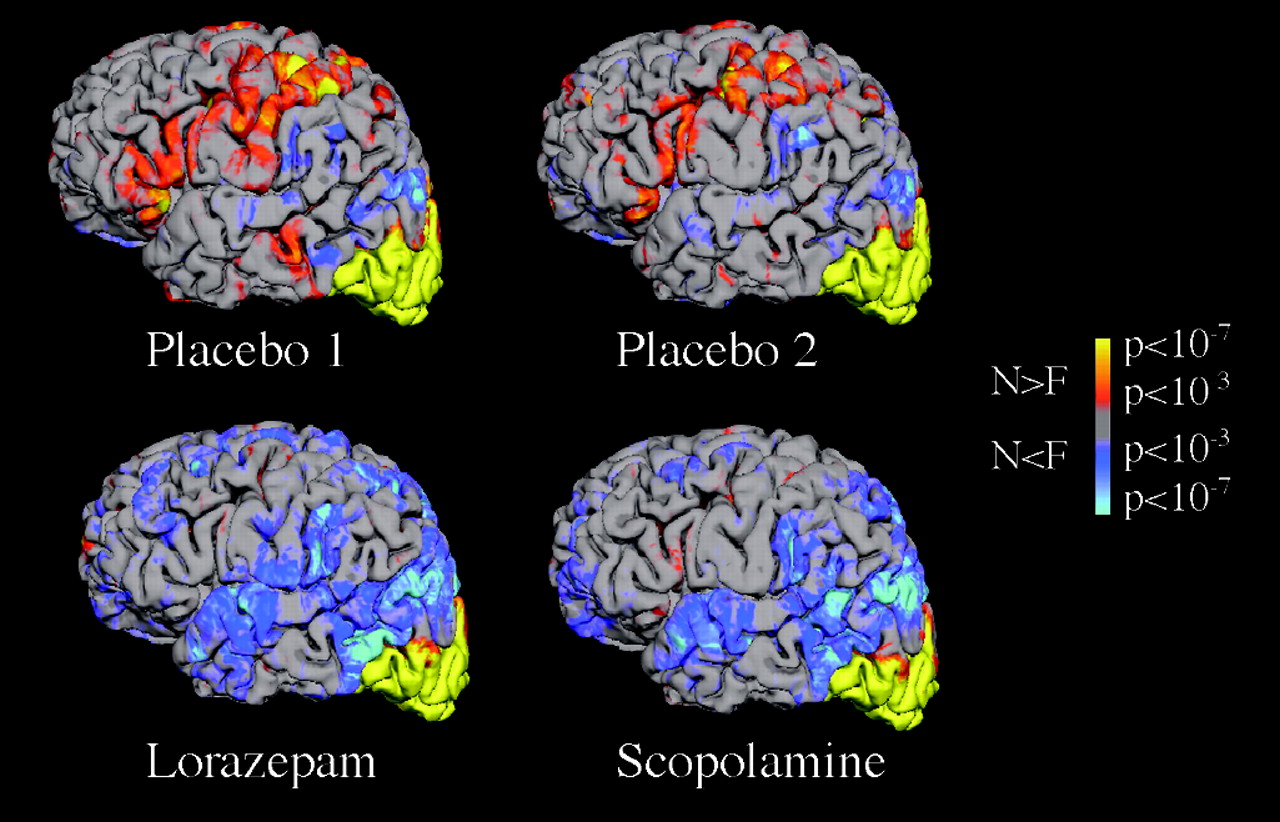

BOOM: What do you think of the studies that have used fMRI scans to support their conclusions that video-games cause aggressive behavior (see Figure 1)?

Dr. Ceranoglu: fMRI is a very sexy technology, it is very appealing [to researchers], but it has important limitations. When you put up a picture of the brain with the lights off that comes from an fMRI scan, it is a very powerful image, but I think, in many ways, we tend to give it too much [authority] than it actually represents. One of the limitations is that when a certain behavior or a certain [behavioral] pattern is happening, [and we observe] this part of the brain lights up more, the [initial] thesis would be, “this part of brain activates when this is happening, ergo, it originates in that part of the brain.” Right? Well, not necessarily so, not all of the time. When we say that a behavior tends to happen with a person [it may be the case] that person’s brain is more reactive in that [specific] area. Or, [ancillary to] this behavior happening, there is also a feedback that is going to provide stimulus that is going to light up that part of the brain more. So, it is not necessarily a unidirectional link.

BOOM: It sounds like what you are saying is that, like the manner in which the behavior is expressed, its formulation can be very individualistic?

Dr. Ceranoglu: Yes. There was an [important] study [recently] in Germany. They showed in 150 plus adolescents, increased activity in certain segments of the brain among those players who tended to play heavily, [such as] those who played nine hours or more a week. It’s [called] the “Kuhn’s study.”[1]

They noticed that, children who [had a higher reactivity] in that part of the brain, ended up playing more than others. That [brain] activity was most likely a pre-existing condition. So, there are some kids who are more predisposed to play in a problematic way.

BOOM: Very interesting.

Dr. Ceranoglu: So in this conversation we already have departed from where we started off talking about violence, and now we are talking about the cognitive effects of the video games, which is the conversation I think we should be having anyway.

BOOM: No arguments here.