As spring approached in 1786, Jeremy Bentham (Figure 10) found himself at the end of a long, arduous journey that began seven months earlier and had taken him from his home in England through France to Italy, where he then sailed the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas to Constantinople, (modern Istanbul). From there, he traveled overland through Bucharest to finally reach his destination in the town of Krichev, in what is today the city of Krychaw on the eastern border of Belarus.

The purpose for his voyage was to visit his brother Samuel, who had made the same trek some six years earlier and had subsequently come into the employ of the Russian prince Grigory Potemkin (see Figure 11). As a highly trained naval engineer, Samuel had been given the job of overseeing the workforce and productivity of various ‘manufactories’ the Prince had constructed throughout the region, something that interested his brother Jeremy a great deal. For back at home, a similar issue related to population management was now threatening the health and welfare of his beloved England from within, that of what to do with the increasing population of convicted criminals.

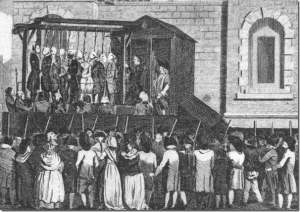

Since the late-17th century, England’s penal law (known as the “Bloody Code”) had sought to discourage the criminal element amongst its citizens by increasing the number of crimes punishable by the hangman’s noose (see Figure 12). By 1750, the number had grown from 50 to 160. At the end of the 18th century, it had risen to over 220.

But in spite of its draconian measures, the Bloody Code from a practical sense, was a dog with all bark and no bite. In fact, only a small percentage of those sentenced to death, were actually executed. Most had their sentences commuted to any number of alternatives, one in particular had been very popular prior to the American Revolution: deportation to the colonies. The beginning of the American Revolutionary War changed all of that as noted Bentham scholar and author, Dr. Anne Brunon-Ernst in her book, Beyond Foucault: New Perspectives on Bentham’s Panopticon, affirms:

In 1776, the American Declaration of Independence and the consequent War of Independence eliminated the possibility that convicts could be deported to the American colonies. At a time when hundreds of crimes were punishable by death or deportation a policy of deportation to America had been the only means of avoiding prison overcrowding (26).

In response, the British government quickly instituted a “stop-gap” measure in which future convicts would be housed on so-called, “hulks,” huge frigates moored on the river Thames and converted into “prison ships” (see Figure 13). Quickly, the ships became overcrowded with prisoners, and amidst the, “dark, damp and verminous,” conditions diseases soon ran rampant (British Library Online, web). According to the website, Royal Arsenal History, “During the first 20 years of their establishment (1776 – 1796), the hulks received around 8000 convicts. Almost one in four of these died on board. Hulk fever, a form of typhus that flourished in dirty, crowded conditions, was rife, as was pulmonary tuberculosis.

![Figure 18 The "convict hulk", “almost one in four [prisoners]…died on board.”](http://www.boomsalad.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Figure18Theconvicthulk-300x189.jpg)

By 1786, public and political outrage at the inhumane conditions of the prisoners had led to a national debate on the problem of inmate treatment and housing, and the British penal system in general, a subject Jeremy had already spent quite a bit of his academic and professional career researching and writing.

Thus it was with keen interest that he observed the unique model of resource management his brother had implemented at the Prince’s workshops (see Figure 14).

Samuel had discovered that by arranging the workspace of his laborers in a circle, in which he as manager stood in the center, he was able to monitor their efforts more efficiently. Moreover, he found that the workers could be more easily trained and his staff of supervisors more easily supervised. The scheme was nothing less than revolutionary, or so thought his brother Jeremy. For while Samuel may have seen within his design a novel and effective solution to a management issue, Jeremy, as the passionate utilitarian he was, saw the future of criminal incarceration.