The “Poor Laws” were instituted in England around the beginning of the 17th century, and were an effort to isolate and contain poverty through social welfare programs typically administered by the parish of the pauper’s birth, and paid for by a public tax known as, “poor rates” At the end of the century, “workhouses” had been established in an effort to put the poor to work and help offset the cost of their upkeep. By 1786, parish resources were strained to their limits, and the rising cost of caring for the poor, paid by means of rising “poor rates,” eventually led public and political sentiment to turn against the “Poor Laws” and in effect, the poor themselves:

The [Poor Laws] indeed have made provision for…relief [of the poor], and the [taxes]…which are collected for their support [“are more than liberal.”]; but…the money collected…does little more than give encouragement to idleness and vice… These laws, so beautiful in theory, promote the evils they mean to remedy, and aggravate the distress they were intended to relieve…It has been most unfortunate for us, that two of the greatest blessings have been productive of the greatest evils. The [American] Revolution gave birth to that enormous load of debt, under which this nation groans; and to the Reformation we are indebted for the [Poor Laws] which multiply the poor. – Joseph Townsend, A Dissertation on Poor Laws, 1786.

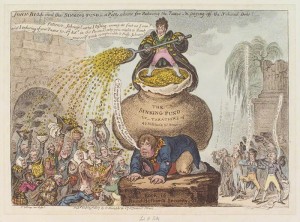

Since the end of the Seven Years’ War, the English national debt had grown dramatically, largely the result of financing the American Revolutionary War effort. That loss also brought a permanent end to the rule of British tax law over the colonies. No longer could the government rely on colonial tax revenues to buffet its flagging economy, and to add insult to injury, after the war was over, millions of pounds of outstanding, colonial debt owed to British lenders would be left unpaid with no effective legal recourse for remuneration. The response of Parliament was to do what they had done so many times before, increase the taxes on its citizens, including the “poor rates” (see Figure 20).

By 1793, a perfect storm of tax-overburden, crop failure, the rapid and dramatic loss of ‘public’ and ‘private’ wealth, a wide scale default on loans, and the final straw, a French Declaration of War, all colluded in a free-fall in consumer confidence, resulting in Great Britain’s, “worst economic crises of the century”.

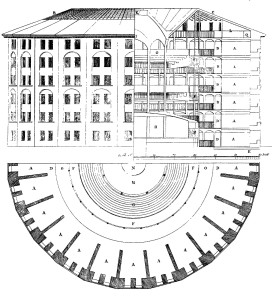

People lost their livelihoods over night and soon the “workhouses,” like the prison barges lying in the muck just outside the city of London, were overflowing. Bentham’s solution: Panopticon, or what Brunon-Ernst identifies as, “the pauper-Panopticon.”

Like the prison, the pauper-Panopticon would satisfy the fundamental utilitarian principle of, “the greatest happiness of the greatest number,” including the inmates who lived within its rounded outer wall (see Figure 21).